All the examples of asemic writing here were created while listening to specific songs — this one was Bob Dylan's 'I Want You'.

As a studio, we constantly explore the possibilities of letterforms: whether it’s creating bespoke lettering for commissioned projects, or playing around with typographic experiments, leftovers and inventions for our self-initiated Adventures in Typography series. This is an ongoing project, so far realised in the form of two journals published by Unit Editions, that documents the many creative journeys that we’ve taken with type. The results play with received ideas of form and often disregard typographic ‘rules’; they use found objects, mix digital and analogue media, and defamiliarise the letters we think we know.

One instinctive way of describing this is with the term ‘abstract typography’. Abstract in the sense that it’s something other than functional, instead taking a conceptual approach to lettering. More concerned with expression than with pure legibility, many of these letters operate at the edge of representation, luxuriating in form and texture. For us part of the value of abstraction in type is that, aside from being entertaining, it can be productively challenging, offering freedom from convention or cliche to open up new visual possibilities.

But what about a kind of typography that is abstract in the truest sense, that genuinely abandons representation or the intent to communicate? Graphic design is familiar with the idea of ‘meaningless’ text, even if we tend not to think about it too much: lorem ipsum placeholder text, for example, a corrupted extract of a real Latin work which renders it nonsensical; or the ‘random’ text used for some typeface samples, where writing is important for visual, rather than semantic, purposes, and so the result is often text culled from other sources: newspaper headlines, technical information, fragments of what might be poetry.

Into this mix we might add the phenomenon or concept known as asemic writing. This term sits somewhere between vague description and genre definition, and marks one logical end-point of what we call abstract typography: writing without language, deliberately ‘meaningless’ notations that are nonetheless somehow identifiable as or reminiscent of writing. (Etymologically, ‘asemic’ means ‘without signs’; in a sense this abstract writing is the opposite of the real alphabet, which has its roots in representations of recognisable objects.) This is a seemingly contradictory or nonsense gesture with a surprisingly creative history; the term ‘asemic writing’ was coined in the 1990s, by the visual poets Tim Gaze and Jim Leftwich, but if you look for them, you can find examples from far earlier, carried out under other names or no name at all. Whether as a hidden artistic genre or as a temporarily convenient label, asemic writing brings together and crosses the boundaries of typography, graphics, conceptual art and avant-garde literature.

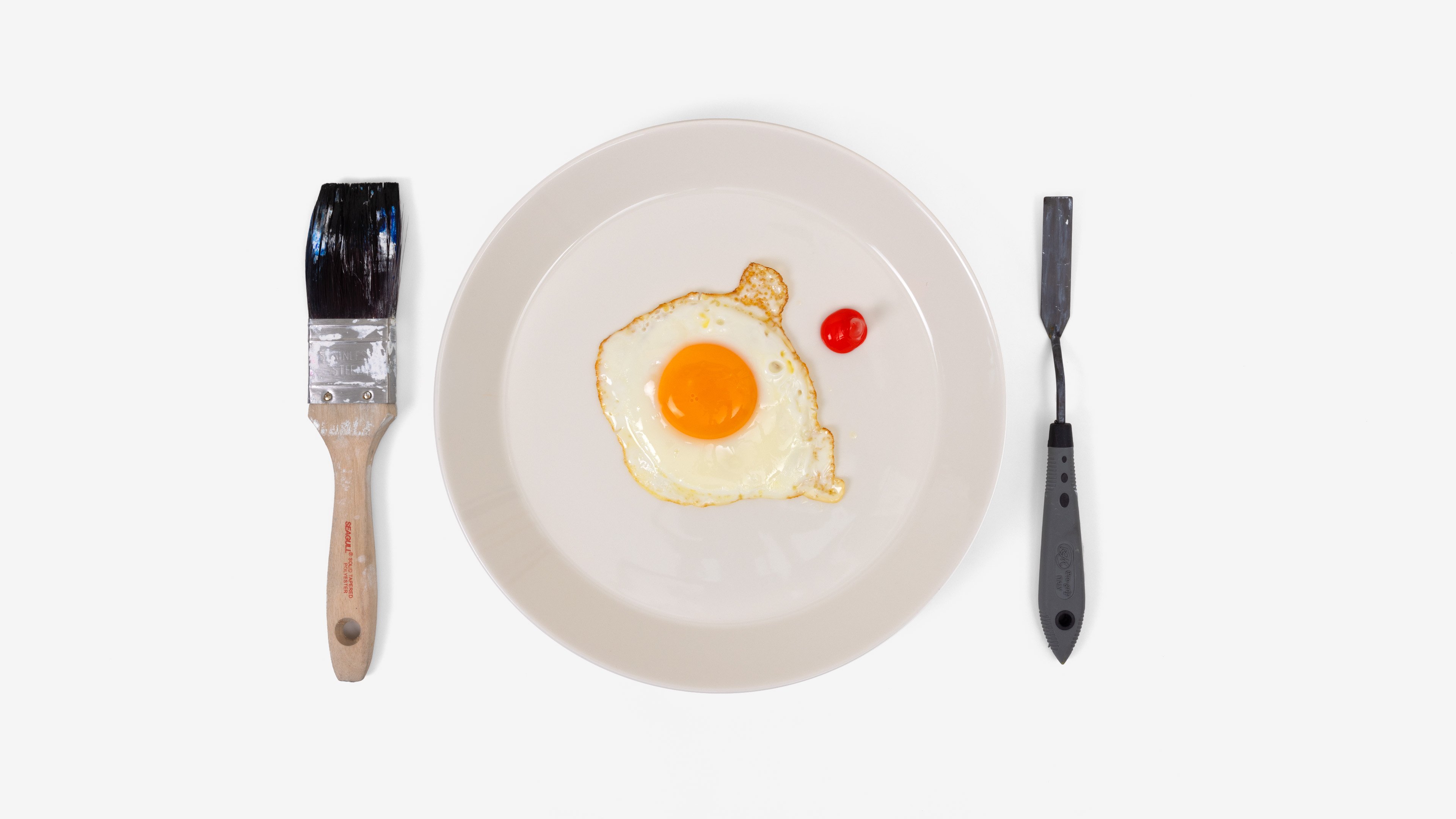

John Cale, 'Paris 1919'.

It came of age more or less in the early twentieth century, at a time when (as the academic Natalie Ferris points out) language and ‘the sign’ became widespread subjects of exploration and study: from stream-of-consciousness novels and abstract art to Ferdinand de Saussure’s new science of ’semiology’ and Freudian psychoanalysis — in which the mind, with all its signs standing in for other things, is structured like a language. Among its most devoted practitioners was Henri Michaux, a Belgian-born French writer, artist, Surrealist and psychonaut. Works like Alphabet (1925) and Narration (1927), both through their suggestive titles and their appearance as a series of strange scribbles and glyphs, give the impression of hidden or coded meaning, lost texts that we would want to decipher, if only we knew how. Max Ernst’s later collaboration with the Georgian poet and publisher Ilia Zdanovich, known as Iliazd, on the artist’s book Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy does something similar, combining handwriting resembling invented hieroglyphs with astrological imagery to suggest an unknown language representing areas of the universe beyond human perception.

A more unusual take on the idea of hidden or secret meaning of asemic writing comes from JB Murray, who had a religious vision aged 70 and began creating asemic paintings which he once described as “the language of the Holy Spirit, direct from God” — echoing the ‘Celestial alphabet’ apparently transmitted by angels to the 16th-century magicians John Dee and Edward Kelley during their occult experiments. Indecipherable writing, however, doesn’t have to be connected to ideas of secrecy, mysticism and the occult. An alternative approach would be something like the ‘hypergraphs’ of Isidore Isou, the founder of Lettrism, whose combination of writing and visual art reached for a new visual language entirely, one that could supposedly combine visuals and text for an ideal, universal mode of communication.

The contrast between these works speaks to an open question at the heart of ‘asemic’ projects: whether this strange hybrid of writing and art is about finding new kinds of communication, or about exploring what might happen if art gives up the idea of communication altogether. Hence the tendency of some artists with backgrounds in better-known varieties of non-representative art to venture into this territory: Wassily Kandinsky, whose ‘Indian Story’ could be read as one example, or Jiro Yoshihara, who was strongly involved with Japan’s Gutai movement. Contrary to abstract art’s often-mythologised virtues of spontaneity or ‘action’, the work of artists such as Cecil Touchon, Irma Blank, Mirtha Dermisache and Ana Hatherly — all of whom are among the most prolific ‘asemic writers’ — has a much more meticulous quality. Combining the visual deliberateness of writing with the ambiguous significance of abstract art, there’s an irony at play here: these oddly beautiful works look like they were painstaking to craft, but their meaning, in the traditional sense, remains far from clear. These artists look for ways that ‘writing’, in the broadest sense, can communicate outside of language — perhaps turning it into something like graphic design. Several projects take inspiration from the visual appeal of traditional calligraphy and writing systems: the Beat-associated artist Brion Gysin’s Calligraphie, or the Chinese artist Xu Bing’s A Book from the Sky, composed of 4000 meaningless characters designed to represent traditional Chinese writing.

The Byrds, 'Everybody's Been Burned'.

The contrasts between the offhand or meaningless and the deliberate or meaningful seem to come to a head in the work of Cy Twombly, a former US army cryptographer who traded one career in experimental writing systems and occluded meaning for another. His art often engages with or includes writing, whether in the form of names and words left haphazardly on the canvas for reasons that are hard to pin down (Twombly once said he was “a little too vague” to be successful in his former job); or as ‘asemic’ scrawls and gestures that approximate or pose as writing within a painting or drawing. Twombly was a subject of fascination for the French writer Roland Barthes. “TW,” he once wrote (using his unexplained but possibly cryptography-inspired codename for Twombly), “has his own way of saying that the essence of writing is neither a form nor a usage but only a gesture.” For Barthes, Twombly successfully reduced — or clarified — writing to its “essence”, which is not in its meaning, or even in its formal appearance, but simply in the physical act of inscription.

Here writing is not an act of communication, but simply of leaving a trace; and it doesn’t need to be deliberate, or meaningful, or any of the qualities we normally invest it with. As he wrote in a separate essay, on the artist André Masson, “for writing to be manifested in its truth (and not in its instrumentality) it must be illegible.” Barthes himself had attempted something similar a few years earlier: his own works of asemic writing, which he titled Contre-Écritures (‘anti-writings,’ or ‘counter-writings’) had been published in the journal Luna-Park alongside works by Gysin and Dermisache (who he sent a hugely admiring letter in 1971). Barthes’ fascination with asemic writing (though he never used the term) is an interesting footnote in modern literary history. One of his spiritual heirs, the theorist Jacques Derrida, had in a typically cryptic essay once described or imagined a radical, ideal kind of writing: “not a writing which simply transcribes, a stony echo of muted words, but a lithography before words”. Writing as marks, not meaning. Barthes and Derrida, two of the most important figures in modern literature, had both sought to theorise a ‘writing’ that was somehow separated from language. ‘Asemic writing’ is, from one angle, the fulfilment of their dream.

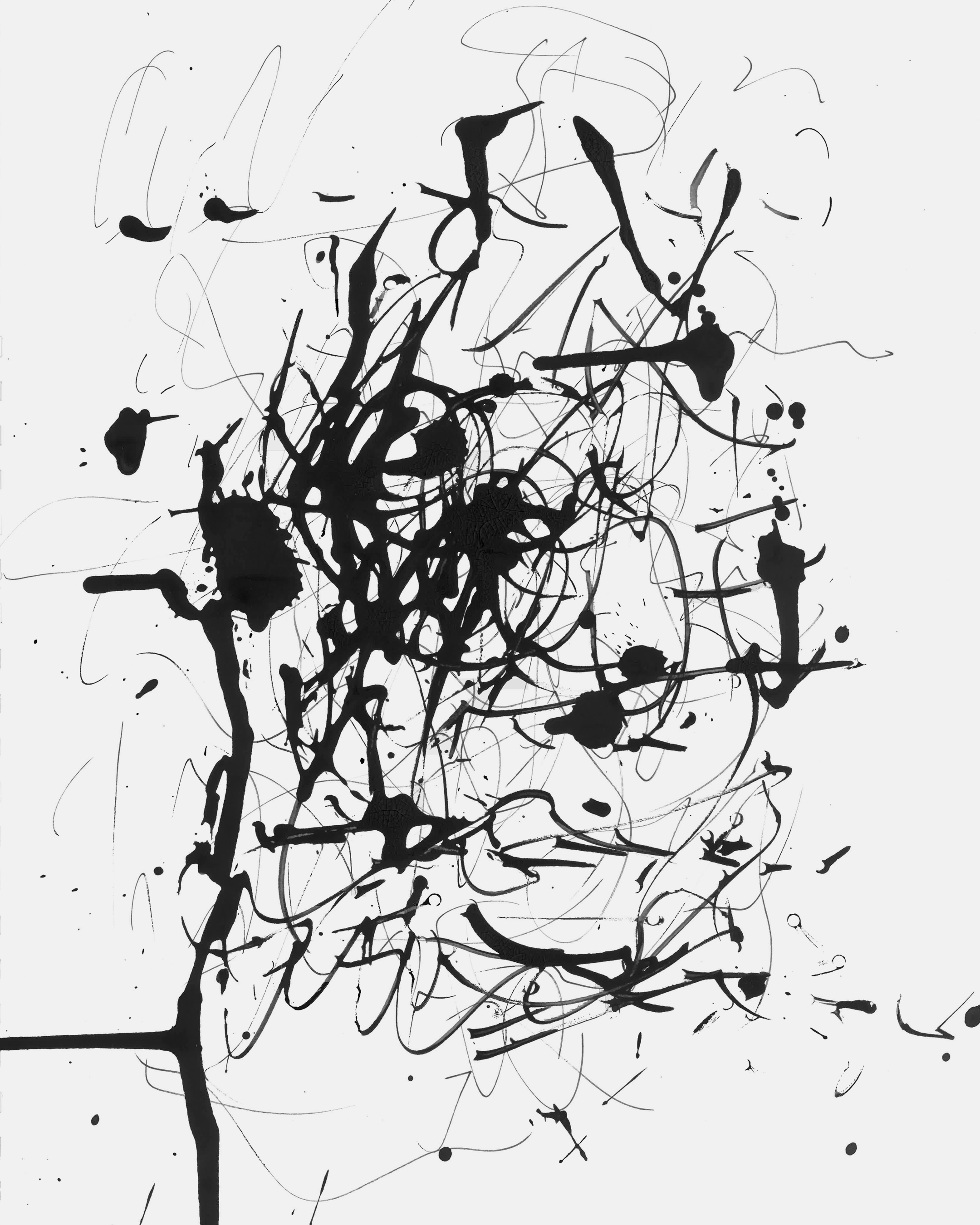

Nick Drake, 'Hazey Jane II'.

To adapt a phrase from Barthes, perhaps asemic writing is a kind of ‘writing degree zero’, or typography degree zero — pure form, before the lines and shapes of writing have become attached to meaning. In this respect it brings to mind other twentieth-century literary experiments, avant-garde interactions in which text is divorced from conventional notions of narrative or meaning: the fluid fields of ‘concrete’ or ‘visual’ poetry, in which writing becomes as much visual as verbal; or Dan Graham’s endlessly repeatable Poem, first published in Aspen magazine in 1966, which consists solely of a precise list of all its components — adjectives, nouns, paper, paper stock, type size. And there’s a scrap of paper from the archives of the nineteenth-century American poet Emily Dickinson, on which is written a wordless ‘poem’, several lines of furious scribbles, the kind of marks you make when testing a pen that seems to have run out of ink. It’s no great distance to travel from this ‘text’ to her actual poetry, which was similarly composed on the backs of envelopes and other seemingly incidental scraps, and which often defied the conventional habits of sense-making. With these scribbles, her writing finally collapses entropically into the semantic void that it always seemed to teeter over.

Here, as in asemic works, writing comes to refer to nothing other than itself — any ‘attribute’ it has is strictly material. Although it’s probably best understood less as a genre or coherent movement than as a loose expression of the affinities between examples like these, asemic writing poses some fun questions. With such a flexible definition of what writing is, what else can we consider ‘writing’ that isn’t normally understood or intended as such? The land art of Richard Long, or the ‘altered landscapes’ of John Pfahl? The act of walking on sand? Watering a plant? At what point do our categories start to break down entirely? Like lorem ipsum and typeface sample text, asemic writing possesses the visual rhythm and appearance — the traces — of writing, while lacking its typically essential communicative ability. Or perhaps it suggests that that’s all writing is: rhythms, appearances and traces, always concealing as much as it reveals.

The Velvet Underground, 'Oh! Sweet Nuthin''.